Badlands National Park

Southwestern SD

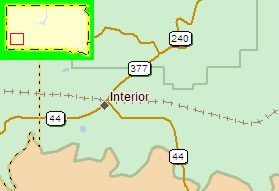

Interior, SD

July 08, 2006

While we were staying in Wall, SD we saw

brochures on nearby Badlands National Park. Since we had been to Roosevelt

National Park in the North Dakota Badlands we thought we would drive down and

see this area.

While we were staying in Wall, SD we saw

brochures on nearby Badlands National Park. Since we had been to Roosevelt

National Park in the North Dakota Badlands we thought we would drive down and

see this area.

Located in southwestern South Dakota, Badlands National Park consists of

nearly 244,000 acres of sharply eroded buttes, pinnacles and spires blended with the largest, protected mixed grass prairie in the United States.

Sixty-four thousand acres are designated official wilderness. Sage Creek Wilderness is the site of the reintroduction of the black-footed ferret,

the most endangered land mammal in North America. The Stronghold Unit is co-managed with the Oglala Sioux Tribe and includes the sites of 1890's

Ghost Dances.

includes the sites of 1890's

Ghost Dances.

Established as Badlands National Monument in 1939, the area was redesignated as a National Park in 1978. Over 11,000 years of human history pales to the

eons old paleontological resources. Badlands National Park contains the world's richest Oligocene epoch fossil beds, dating 23 to 35 million years old.

The evolution of mammal species such as the horse, sheep, rhinoceros and pig can be studied in the Badlands formations.

The bizarre landforms called the badlands are, despite the

uninviting name, a masterpiece of water and wind sculpture. They are near

deserts of a special kind, where rain is infrequent, the bare rocks are poorly

consolidated and relatively uniform in their resistance to erosion, and runoff

water washes away large amounts of sediment. On  average, the White River

Badlands of South Dakota erode one inch per year. They are formidable redoubts

of stark beauty where the delicate balance between creation and decay, that

distinguishes so much geologic art, is manifested in improbable landscapes -

near moonscapes - whose individual elements seem to defy gravity. Erosion is so

rapid that the landforms can change perceptibly overnight as a result of a

single thunderstorm.

average, the White River

Badlands of South Dakota erode one inch per year. They are formidable redoubts

of stark beauty where the delicate balance between creation and decay, that

distinguishes so much geologic art, is manifested in improbable landscapes -

near moonscapes - whose individual elements seem to defy gravity. Erosion is so

rapid that the landforms can change perceptibly overnight as a result of a

single thunderstorm.

At Badlands National Park, weird shapes are etched into a plateau of soft

sediments and volcanic ash, revealing colorful bands of strata. The

stratification adds immeasurably to the beauty of each scene, binding together

all of its diverse parts. Viewed horizontally, individual beds are traceable

from pinnacle to pinnacle, mound to mound, ridge to ridge, across the

intervening ravines. Viewed from above, the bands curve in and out of the valley

like contour lines on a topographic map. A geologic story is written in the

rocks of Badlands National Park, every bit as fascinating and colorful as their

outward appearance. It is an account of 75 million years of accumulation with

intermittent periods of erosion that began when the Rocky Mountains reared up in

the West and spread sediments over vast expanses of the plains. The sand, silt,

and clay, mixed and inter-bedded with volcanic ash, stacked up, layer upon

flat-lying layer, until the pile was thousands of feet deep. In a final phase of

volcanism as the uplift ended, white ash rained from the

Viewed horizontally, individual beds are traceable

from pinnacle to pinnacle, mound to mound, ridge to ridge, across the

intervening ravines. Viewed from above, the bands curve in and out of the valley

like contour lines on a topographic map. A geologic story is written in the

rocks of Badlands National Park, every bit as fascinating and colorful as their

outward appearance. It is an account of 75 million years of accumulation with

intermittent periods of erosion that began when the Rocky Mountains reared up in

the West and spread sediments over vast expanses of the plains. The sand, silt,

and clay, mixed and inter-bedded with volcanic ash, stacked up, layer upon

flat-lying layer, until the pile was thousands of feet deep. In a final phase of

volcanism as the uplift ended, white ash rained from the  sky to frost the cake,

completing the building stage.

sky to frost the cake,

completing the building stage.

Broad regional uplift raised the land about 5 million years ago and initiated

the erosion that created the Badlands. The White River, which now flows west to

east five or ten miles south of the park, eroded a scarp, the beginning of what

is now called the Wall. Numerous small streams furrowed the scarp face

and eventually intersected to create the Badlands topography. Each rainstorm

over the next 5 million years chewed away at the Wall, making its crest recede

northward away from the river as its base followed suit. This is an old story in

the arid and semi-arid regions of the West. It always happens in rocks that are

relatively non-resistant to erosion and it always starts with a scarp.

At Badlands National Park, the White River produced the scarp. The physical

character of the Badlands varies considerably according to the nature of the

materials. For example, the frosting of volcanic ash at Badlands National Park

succumbs quickly as the Wall advances northward into the upper plain - the

original land surface - exposing the more durable underlying beds of the Brule

formation. Nature's answer to great resistance is to carve steeper slopes,

resulting here in incredibly slender spires above knife-sharp ridges and

intricately creased slopes. Deeper into the layer cake, the more rounded ridges

and spurs, and gentler slopes, reflect the softer mudstone of the Chadron

formation. Numerous "islands" of Chadron mudstone dot the plain in

front of the Wall. They look like nothing more than mud mounds, except for their

striking color-banding which matches perfectly that of the base of the Wall.

They are remnants, soon to be gone, of the earlier, ever changing Badlands.

according to the nature of the

materials. For example, the frosting of volcanic ash at Badlands National Park

succumbs quickly as the Wall advances northward into the upper plain - the

original land surface - exposing the more durable underlying beds of the Brule

formation. Nature's answer to great resistance is to carve steeper slopes,

resulting here in incredibly slender spires above knife-sharp ridges and

intricately creased slopes. Deeper into the layer cake, the more rounded ridges

and spurs, and gentler slopes, reflect the softer mudstone of the Chadron

formation. Numerous "islands" of Chadron mudstone dot the plain in

front of the Wall. They look like nothing more than mud mounds, except for their

striking color-banding which matches perfectly that of the base of the Wall.

They are remnants, soon to be gone, of the earlier, ever changing Badlands.

While we were there we happened on to an archeological dig they were conducting.

They called it the Big Pig Dig. An African watering hole in South Dakota? That's what two visitors discovered in

1993 when they found a large backbone sticking from the ground near the Conata Picnic

Area. Many seasons of excavation yielded more than five thousand bones. The largest

belonged to Archaeotherium, a pig-like mammal that lived 37 to 39 million years ago.

While we were there we happened on to an archeological dig they were conducting.

They called it the Big Pig Dig. An African watering hole in South Dakota? That's what two visitors discovered in

1993 when they found a large backbone sticking from the ground near the Conata Picnic

Area. Many seasons of excavation yielded more than five thousand bones. The largest

belonged to Archaeotherium, a pig-like mammal that lived 37 to 39 million years ago.

When the first fossil was discovered at the Pig Dig, park staff thought they had four

days of excavation ahead of them. Because of the wealth of fossils at the site,

field work continued for over a decade.

The Pig Dig presents a mystery: Why did so many animals die in one place? Did the

watering hole dry up suddenly, stranding animals without water? Did sick, injured,

and old animals gather here, too weak to travel far for water?

The Archaeotherium smelled its favorite food: something rotten. A small rhinoceros

called a Subhyracodon had died trapped in the mud of a drying pond. The distant

ancestor of the wild boar hoped for a feast, but fell prey to the sticky mud. Scientists

uncovered its bones some 34 million years later.

We enjoyed watching the young people intent at their tasks. They were very

carefully brushing away the dirt from the bones that were embedded in the dirt.

We enjoyed talking with them about their interests in archaeology and the

long hours they put in to achieve their goals.

We really enjoyed our visit to the Badlands and I would really recommend this to

anyone who enjoys seeing nature in the raw and especially to anyone who is

interested in hiking and/or backpacking.

Good Luck! Have Fun! and Stay Safe!

Laura