Ft. Missoula

Living Historic Museum

Missoula, MT

August 2nd, 2006

As

we drove through Montana one early morning, we passed through Missoula. We

had been here before and were not intending to look further for something

interesting to write about. Laura, however had found something that was of

interest. Old Fort Missoula, just out of town to the southwest. We

decided to ride out that way and see if there was anything there that we could

make a story about. I'm glad we did. We found that the Fort area has

had a distinguished and varied history, ending with its takeover by the

Historical Museum of Missoula in 1975. We parked in front of the

Quartermaster's store, which now serves as the Museum entrance and store.

We decided to take the self-guided tour. From a large sign at the front of

the store we learned that the first troops arrived on June 25, 1877. A

month later, troops and civilian volunteers failed to delay Chief

Joseph of the Nez Perce in his passage North. Shortly thereafter, the

first action seen was under Col. Gibbon at the battle of the Big Hole

where 13 were killed and 14 wounded. That ended, for the most part,

all combat seen in or around the Fort. The Fort went on as a defensive

quarterstone

for Western Montana, building roads, erecting telegraph lines and escorting

Indians. In 1888 the Fort saw the arrival of a new kind of soldier.

The 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps arrived. It stayed for 10 years but the

bicycle was found to be less than effective under war conditions and the

experiment was ended. The Fort went on to see use as an Alien detention

camp, and for a

As

we drove through Montana one early morning, we passed through Missoula. We

had been here before and were not intending to look further for something

interesting to write about. Laura, however had found something that was of

interest. Old Fort Missoula, just out of town to the southwest. We

decided to ride out that way and see if there was anything there that we could

make a story about. I'm glad we did. We found that the Fort area has

had a distinguished and varied history, ending with its takeover by the

Historical Museum of Missoula in 1975. We parked in front of the

Quartermaster's store, which now serves as the Museum entrance and store.

We decided to take the self-guided tour. From a large sign at the front of

the store we learned that the first troops arrived on June 25, 1877. A

month later, troops and civilian volunteers failed to delay Chief

Joseph of the Nez Perce in his passage North. Shortly thereafter, the

first action seen was under Col. Gibbon at the battle of the Big Hole

where 13 were killed and 14 wounded. That ended, for the most part,

all combat seen in or around the Fort. The Fort went on as a defensive

quarterstone

for Western Montana, building roads, erecting telegraph lines and escorting

Indians. In 1888 the Fort saw the arrival of a new kind of soldier.

The 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps arrived. It stayed for 10 years but the

bicycle was found to be less than effective under war conditions and the

experiment was ended. The Fort went on to see use as an Alien detention

camp, and for a while a POW camp for Italian prisoners. It still sees an occasional

professional soldier on its parade field. Both the Montana Reserve and

the Montana National Guard use the land. The static displays inside the

small museum told the story of early Montana. Back in 1803, Thomas

Jefferson, then President, and visionary, saw the U.S. being hemmed in by other

countries. He was determined to expand the U.S. territories as far west as

he could. Jefferson secured approval for an expedition westward to map and

claim as much land as possible. He chose a man named Meriwether Lewis to

head up the expedition. Jefferson felt strongly that the mission was so

important, that he made

sure that Lewis was trained to undertake scientific investigations, and that he had

the best equipment for measurements and the latest maps, along with the necessary

references books. Jefferson sent Lewis to Philadelphia to receive

instructions from

five scholars who would

while a POW camp for Italian prisoners. It still sees an occasional

professional soldier on its parade field. Both the Montana Reserve and

the Montana National Guard use the land. The static displays inside the

small museum told the story of early Montana. Back in 1803, Thomas

Jefferson, then President, and visionary, saw the U.S. being hemmed in by other

countries. He was determined to expand the U.S. territories as far west as

he could. Jefferson secured approval for an expedition westward to map and

claim as much land as possible. He chose a man named Meriwether Lewis to

head up the expedition. Jefferson felt strongly that the mission was so

important, that he made

sure that Lewis was trained to undertake scientific investigations, and that he had

the best equipment for measurements and the latest maps, along with the necessary

references books. Jefferson sent Lewis to Philadelphia to receive

instructions from

five scholars who would  round

out his knowledge in mapping methods. During this time Lewis learned how to use

a chronometer, and how to take observations with it. This required Lewis

to adapt standard methods of measurements for use in the wilderness, including

the making of an artificial horizon when the sun was not available. Lewis asked

William Clark, an old frontiersman and Indian fighter to join him and the Lewis

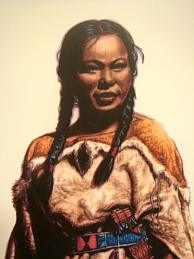

and Clark Expedition was created. One of the most remembered people on the

trip was Sacagawea, a 17 year old Shoshone girl who's husband, a French fur

trapper named Charbonneau, served as a translator. She joined the group at

Fort Mandan, near present day Washburn, North Dakota. After the expedition, she was invited

by Lewis to live in Saint Louis where she stayed until she died of the fever in

1825. A likeness of her can be found on the U.S. gold dollar by the same

name. There were many

round

out his knowledge in mapping methods. During this time Lewis learned how to use

a chronometer, and how to take observations with it. This required Lewis

to adapt standard methods of measurements for use in the wilderness, including

the making of an artificial horizon when the sun was not available. Lewis asked

William Clark, an old frontiersman and Indian fighter to join him and the Lewis

and Clark Expedition was created. One of the most remembered people on the

trip was Sacagawea, a 17 year old Shoshone girl who's husband, a French fur

trapper named Charbonneau, served as a translator. She joined the group at

Fort Mandan, near present day Washburn, North Dakota. After the expedition, she was invited

by Lewis to live in Saint Louis where she stayed until she died of the fever in

1825. A likeness of her can be found on the U.S. gold dollar by the same

name. There were many  other

things of interest in the museum but the day was passing and it was time to see

the outside. There are three original buildings on the property. One

that was of interest to me was the old St. Michael's church. According to the

handout provided by the museum store, the church served the area's settlers. In

1873 a government survey disclosed that the Jesuits and a local farmer both claimed the same 40 acres of land,

so the church was moved by wagon to Missoula. It stood on the grounds of St. Patrick Hospital for many years before it was returned to the site of old Hell Gate in 1962. The Friends of the Historical

Museum at Fort Missoula moved the church to the museum grounds. Further

out to the east, we arrived at the barracks used for Italian POWs during WWII.

The handout advised that Alien Detention Center Barracks, which were built in 1941, were moved to the

museum grounds in 1995. The wooden barracks we were looking at was one of several wooden barracks constructed

by Italian internees, detained at Fort Missoula between 1941 and 1944. This

turned out to be one of the more unusual incarcerations of the war. In 1941

at the onset of the War, Roosevelt, using a 1917 sabotage act seized commercial

ships flying

other

things of interest in the museum but the day was passing and it was time to see

the outside. There are three original buildings on the property. One

that was of interest to me was the old St. Michael's church. According to the

handout provided by the museum store, the church served the area's settlers. In

1873 a government survey disclosed that the Jesuits and a local farmer both claimed the same 40 acres of land,

so the church was moved by wagon to Missoula. It stood on the grounds of St. Patrick Hospital for many years before it was returned to the site of old Hell Gate in 1962. The Friends of the Historical

Museum at Fort Missoula moved the church to the museum grounds. Further

out to the east, we arrived at the barracks used for Italian POWs during WWII.

The handout advised that Alien Detention Center Barracks, which were built in 1941, were moved to the

museum grounds in 1995. The wooden barracks we were looking at was one of several wooden barracks constructed

by Italian internees, detained at Fort Missoula between 1941 and 1944. This

turned out to be one of the more unusual incarcerations of the war. In 1941

at the onset of the War, Roosevelt, using a 1917 sabotage act seized commercial

ships flying  Italian

and German flags. The crews were left aboard but became bored and began

damaging the ships. To prevent this the crews were removed and offered to be

returned to their respective countries. Most resisted this idea and were

offered incarceration for the duration of the war. As they had fought

deportation, they were considered very low security risk, and were given great

liberties in the camps where they stayed. At the end of the War they were

simply sent home, with many of them turning right around and returning back to

the US to become citizens. The plight of the Japanese Americans was not so

easy. Those living on the west coast were considered dangerous and were

rounded up for their own protection and placed in similar camps. An interesting

side note to this was a small sign which stated that the Japanese, both American

and Nationals who were living in Hawaii were not incarcerated. It seems

that when making the decision, the local government realized that if the Japanese

were removed from the work force, it would hurt the war effort so no Japanese

were picked up in Hawaii. Go figure.

Italian

and German flags. The crews were left aboard but became bored and began

damaging the ships. To prevent this the crews were removed and offered to be

returned to their respective countries. Most resisted this idea and were

offered incarceration for the duration of the war. As they had fought

deportation, they were considered very low security risk, and were given great

liberties in the camps where they stayed. At the end of the War they were

simply sent home, with many of them turning right around and returning back to

the US to become citizens. The plight of the Japanese Americans was not so

easy. Those living on the west coast were considered dangerous and were

rounded up for their own protection and placed in similar camps. An interesting

side note to this was a small sign which stated that the Japanese, both American

and Nationals who were living in Hawaii were not incarcerated. It seems

that when making the decision, the local government realized that if the Japanese

were removed from the work force, it would hurt the war effort so no Japanese

were picked up in Hawaii. Go figure.