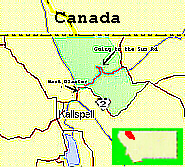

Montana is a wonderful state, and should be on the “must

see” list of any traveler to the north west. The human

history is just short of unbelievable with its Indian

tribes and heritage, its boom towns like Billings and

Butte. Where would Zane Gray or Jimmy Stewart be without

the influence of this wide open cowboy and Indian land.

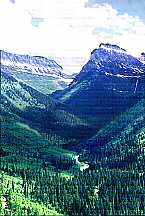

Still the greatest story every told in this land began

millions of years ago when a giant glacier carved out a

huge swath of land in the upper Waterton Valley. When the

glacier receded, wind, snow and rain, worked with the

ever present pressure of the rivers to cut the land up

into one of the most dramatic landscapes in North

America. The Glacier National Park, which makes up the

large southern part consists of 1.2 million acres and

includes 50 glaciers, 200 lakes and 700 miles of hiking

trails.

Montana is a wonderful state, and should be on the “must

see” list of any traveler to the north west. The human

history is just short of unbelievable with its Indian

tribes and heritage, its boom towns like Billings and

Butte. Where would Zane Gray or Jimmy Stewart be without

the influence of this wide open cowboy and Indian land.

Still the greatest story every told in this land began

millions of years ago when a giant glacier carved out a

huge swath of land in the upper Waterton Valley. When the

glacier receded, wind, snow and rain, worked with the

ever present pressure of the rivers to cut the land up

into one of the most dramatic landscapes in North

America. The Glacier National Park, which makes up the

large southern part consists of 1.2 million acres and

includes 50 glaciers, 200 lakes and 700 miles of hiking

trails.

The history of the park actually started back in 1818

when the 49th parallel to the continental Divide was

established as the international boundary between the

territory o f the United States and what was at that time,

the territory owned by Great Britain. In 1895 the

northern fourth of the area became the Waterton Lakes

National Park by an act of the Canadian Congress. The lower three fourths became Glacier National Park on May

11, 1910 by an act of the US Congress. At that time

there were only a few miles of rough wagon roads. In

1932, largely through the efforts of Rotary International

of Alberta and Montana, the governments of both countries

established the first international park. The

“Waterton/Glacier International Peace Park” as it is

known today. It has been named by the United Nations, as

a “Heritage Park”. One of only seven parks in the world

to be so designated.

f the United States and what was at that time,

the territory owned by Great Britain. In 1895 the

northern fourth of the area became the Waterton Lakes

National Park by an act of the Canadian Congress. The lower three fourths became Glacier National Park on May

11, 1910 by an act of the US Congress. At that time

there were only a few miles of rough wagon roads. In

1932, largely through the efforts of Rotary International

of Alberta and Montana, the governments of both countries

established the first international park. The

“Waterton/Glacier International Peace Park” as it is

known today. It has been named by the United Nations, as

a “Heritage Park”. One of only seven parks in the world

to be so designated.

Driving up from Missoula Montana, past Flathead Lake, we

arrived in West Glacier in early evening. We pulled into

the West Glacier RV park on SR2, a privately-owned RV

park just outside of West Glacier. This was due to the

fact that, although there are a reported 1000 campsites

within the

park, vehicles and vehicle combination longer

than 21 feet and wider than 8 feet are prohibited between

Avalanche Campground and the Sun Point parking area. Our

campsite was nice, clean and very woodsy. The next

morning we ventured into the town of West Glacier.

Somewhat commercial, with the basic necessities. Grocery

store, photo store, restaurant and bar, even a liquor

store. We continued on across the Middle Fork of the

Flathead River to the entrance of Glacier National Park. We were driving on the now famous “Going to the Sun

Road”. A road that took two decades of planning and

construction to become a spectacular

park, vehicles and vehicle combination longer

than 21 feet and wider than 8 feet are prohibited between

Avalanche Campground and the Sun Point parking area. Our

campsite was nice, clean and very woodsy. The next

morning we ventured into the town of West Glacier.

Somewhat commercial, with the basic necessities. Grocery

store, photo store, restaurant and bar, even a liquor

store. We continued on across the Middle Fork of the

Flathead River to the entrance of Glacier National Park. We were driving on the now famous “Going to the Sun

Road”. A road that took two decades of planning and

construction to become a spectacular

reality. When the

park was created, there was much disagreement over what

to do to make it more accessible to travelers. After

overcoming a move to build a road along the railroad that

bordered the south end of the park, Superintendent

William R. Logan’s dream of a transmountain road was

accepted and in 1921 Congress provided the first

appropriation specifically for the park road, in the

amount of one hundred thousand dollars.

In 1924 Frank A. Kittredge of the Bureau of Public Roads conducted a survey of 21 miles over the Continental

Divide

reality. When the

park was created, there was much disagreement over what

to do to make it more accessible to travelers. After

overcoming a move to build a road along the railroad that

bordered the south end of the park, Superintendent

William R. Logan’s dream of a transmountain road was

accepted and in 1921 Congress provided the first

appropriation specifically for the park road, in the

amount of one hundred thousand dollars.

In 1924 Frank A. Kittredge of the Bureau of Public Roads conducted a survey of 21 miles over the Continental

Divide starting in September. Kittredge raced to finish

the survey before winter closed in. His team of 32 men

often climbed 3000 feet each morning to get the survey

sites. The crew walked along narrow ledges and hung over

cliffs by ropes to take many of the measurements. The

work was too challenging for some and Kittridge’s crew

suffered from a 300% labor turnover in the three months

of survey. In cooperation with the National Park

Service, the road was built with minimum impact on the

area. Bridges, retaining walls and guardrails were all

constructed of natural material from the surrounding area

Many exciting moments were spent as construction

companies working from either end worked toward Logan’s

Pass and the Continental Divide. The road was completed

with the first car passing over the 51 miles of crushed

rock road on July 15, 1933. At the official dedication

the name was changed from the Transmountain Road to the

“Going to the Sun Road”, taking it’s name from the nearby

“Going to the Sun Mountain”. It would be 1952 before the

last of the gravel would be replaced with black top.

starting in September. Kittredge raced to finish

the survey before winter closed in. His team of 32 men

often climbed 3000 feet each morning to get the survey

sites. The crew walked along narrow ledges and hung over

cliffs by ropes to take many of the measurements. The

work was too challenging for some and Kittridge’s crew

suffered from a 300% labor turnover in the three months

of survey. In cooperation with the National Park

Service, the road was built with minimum impact on the

area. Bridges, retaining walls and guardrails were all

constructed of natural material from the surrounding area

Many exciting moments were spent as construction

companies working from either end worked toward Logan’s

Pass and the Continental Divide. The road was completed

with the first car passing over the 51 miles of crushed

rock road on July 15, 1933. At the official dedication

the name was changed from the Transmountain Road to the

“Going to the Sun Road”, taking it’s name from the nearby

“Going to the Sun Mountain”. It would be 1952 before the

last of the gravel would be replaced with black top.