Mount St. Helens

A Volcano

Washington

August 12th, 1998

Washington State surely has its unique place in the United

States. For several months a year, it is truly a paradise for

everyone. What would you have? The big city atmosphere of

Seattle, the Puget Sound, the Pacific Ocean, the big forests,

even the mountains. Why, you would say, nothing more than

California has to offer. Ah, but the heart of Washington State

holds it’s uniqueness within the Cascade mountain range.

Here lie the smallest of five major volcanic peaks in this

wonderful state. Mount St. Helens, with an elevation of 9,677

feet (2,950 m) (before the eruption of May 18,1980) is unique in

United States history. But I’m getting ahead of myself. We

had driven up out of Oregon, looking for adventure in the great

state of Washington. It was time for big trees, campfi

Washington State surely has its unique place in the United

States. For several months a year, it is truly a paradise for

everyone. What would you have? The big city atmosphere of

Seattle, the Puget Sound, the Pacific Ocean, the big forests,

even the mountains. Why, you would say, nothing more than

California has to offer. Ah, but the heart of Washington State

holds it’s uniqueness within the Cascade mountain range.

Here lie the smallest of five major volcanic peaks in this

wonderful state. Mount St. Helens, with an elevation of 9,677

feet (2,950 m) (before the eruption of May 18,1980) is unique in

United States history. But I’m getting ahead of myself. We

had driven up out of Oregon, looking for adventure in the great

state of Washington. It was time for big trees, campfi res, and a “get

back to nature” experience. We had stopped at the Ike Kinswa

state park outside of Mossyrock. The next day we took the long

drive around route 12 and stopped at the Mt. St. Helens national

park. The devastation was overpowering. As we wandered through

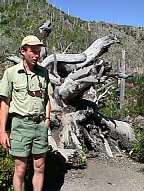

the desolation we came across Ranger Paul Swanson who was about

to give a talk and a walk through a section of park. He opened

his presentation by asking us to back up to March 20, 1980. After

a quiet period of 123 years, earthquake activity once again began

under the Mt. St. Helen's volcano. Seven days later, on March 27,

small phreatic (steam) explosions began. A "bulge"

developed on the north side of Mt. St. Helens as magma pushed up

within the peak. Angle and slope-distance measurements to the

bulge indicated it was growing at a rate of up to five feet (1.5

m) per day. By

res, and a “get

back to nature” experience. We had stopped at the Ike Kinswa

state park outside of Mossyrock. The next day we took the long

drive around route 12 and stopped at the Mt. St. Helens national

park. The devastation was overpowering. As we wandered through

the desolation we came across Ranger Paul Swanson who was about

to give a talk and a walk through a section of park. He opened

his presentation by asking us to back up to March 20, 1980. After

a quiet period of 123 years, earthquake activity once again began

under the Mt. St. Helen's volcano. Seven days later, on March 27,

small phreatic (steam) explosions began. A "bulge"

developed on the north side of Mt. St. Helens as magma pushed up

within the peak. Angle and slope-distance measurements to the

bulge indicated it was growing at a rate of up to five feet (1.5

m) per day. By  May 17, part of the volcano's north side had

been pushed upwards and outwards over 450 feet (135 m). On May

18, at 8:32 a.m. Pacific Daylight Time, a magnitude 5.1

earthquake shook Mt. St. Helens. The bulge and surrounding area

slid away in a gigantic rockslide and debris avalanche, releasing

pressure, and triggering a major pumice and ash eruption of the

volcano. Thirteen hundred feet (400 m) of the peak collapsed or

blew outwards. As a result, a debris avalanche filled 24 square

miles (62 square Km) of the valley. 250 square miles (650 square

km) of recreation, timber, and private lands were damaged by this

lateral blast. An estimated 200 million cubic yards (150 million

cubic meters) of material was deposited directly by lahars

(volcanic mudflows) into the river channels. Fifty-seven people

were killed

May 17, part of the volcano's north side had

been pushed upwards and outwards over 450 feet (135 m). On May

18, at 8:32 a.m. Pacific Daylight Time, a magnitude 5.1

earthquake shook Mt. St. Helens. The bulge and surrounding area

slid away in a gigantic rockslide and debris avalanche, releasing

pressure, and triggering a major pumice and ash eruption of the

volcano. Thirteen hundred feet (400 m) of the peak collapsed or

blew outwards. As a result, a debris avalanche filled 24 square

miles (62 square Km) of the valley. 250 square miles (650 square

km) of recreation, timber, and private lands were damaged by this

lateral blast. An estimated 200 million cubic yards (150 million

cubic meters) of material was deposited directly by lahars

(volcanic mudflows) into the river channels. Fifty-seven people

were killed  or are

still missing. For more than nine hours a vigorous plume of ash

erupted, eventually reaching 12 to 15 miles (20-25 km) above sea

level. The plume moved eastward at an average speed of 60 miles

per hour (95 km/hr), with ash reaching Idaho by noon. By early

May 19, the devastating eruption was over. After the May 18, 1980

eruption, Mount St. Helens' elevation was only 8364 feet (2,550

m) and the volcano had a one-mile-wide (1.5 km) horseshoe-shaped

crater, seen here from the northwest. For weeks, volcanic ash

covered the landscape around the volcano and for several hundred

miles downwind to the east. Noticeable ash fell in eleven states.

The total volume of ash (before its compaction by rainfall) was

approximately 0.26 cubic mile (1.01 cubic km), or enough ash to

cover a football field to a depth of 150 miles (240 km). Th

or are

still missing. For more than nine hours a vigorous plume of ash

erupted, eventually reaching 12 to 15 miles (20-25 km) above sea

level. The plume moved eastward at an average speed of 60 miles

per hour (95 km/hr), with ash reaching Idaho by noon. By early

May 19, the devastating eruption was over. After the May 18, 1980

eruption, Mount St. Helens' elevation was only 8364 feet (2,550

m) and the volcano had a one-mile-wide (1.5 km) horseshoe-shaped

crater, seen here from the northwest. For weeks, volcanic ash

covered the landscape around the volcano and for several hundred

miles downwind to the east. Noticeable ash fell in eleven states.

The total volume of ash (before its compaction by rainfall) was

approximately 0.26 cubic mile (1.01 cubic km), or enough ash to

cover a football field to a depth of 150 miles (240 km). Th e downed trees, over

four billion board feet of usable timber, would have been enough

to build 150,000 homes. The nearly 2/3 cubic miles (2.3 cubic km)

of debris avalanche that slid from the volcano on May 18, is

enough material to cover Washington, D.C. to a depth of 14 feet

(4 m). The avalanche traveled approximately 15 miles (24 km)

downstream at a velocity exceeding 150 miles per hour (240

km/hr). It left behind a hummocky deposit with an average

e downed trees, over

four billion board feet of usable timber, would have been enough

to build 150,000 homes. The nearly 2/3 cubic miles (2.3 cubic km)

of debris avalanche that slid from the volcano on May 18, is

enough material to cover Washington, D.C. to a depth of 14 feet

(4 m). The avalanche traveled approximately 15 miles (24 km)

downstream at a velocity exceeding 150 miles per hour (240

km/hr). It left behind a hummocky deposit with an average  thickness of 150 feet (45 m) and a maximum thickness of 600 feet

(180 m). More than 200 homes and over 185 miles (300 km) of roads

were destroyed by the 1980 lahars. During the May 18, 1980

eruption, at least 17 separate pyroclastic flows descended the

flanks of Mt. St. Helens. Pyroclastic flows typically move at

speeds of over 60 miles per hour (100 km/hr) and reach

temperatures of over 800° Fahrenheit (400° Celsius). This was

truly one of nature’s greatest destructive acts in North

America. But like nature’s ability to destroy itself, it

most assuredly will recreate itself. Just months after the fatal

blast, the fireweed appeared. That resilient plant that sprouts

after every northwestern forest fire. Those who, having not seen

this destruction, and wishing to witness the carnage, will have

to do so within the next few decades. Otherwise nature will have

licked its wounds and recovered its devastation. Soon the

land will again be covered with spruce, cedar and alder, and all

signs except the gigantic crater will have vanished.

thickness of 150 feet (45 m) and a maximum thickness of 600 feet

(180 m). More than 200 homes and over 185 miles (300 km) of roads

were destroyed by the 1980 lahars. During the May 18, 1980

eruption, at least 17 separate pyroclastic flows descended the

flanks of Mt. St. Helens. Pyroclastic flows typically move at

speeds of over 60 miles per hour (100 km/hr) and reach

temperatures of over 800° Fahrenheit (400° Celsius). This was

truly one of nature’s greatest destructive acts in North

America. But like nature’s ability to destroy itself, it

most assuredly will recreate itself. Just months after the fatal

blast, the fireweed appeared. That resilient plant that sprouts

after every northwestern forest fire. Those who, having not seen

this destruction, and wishing to witness the carnage, will have

to do so within the next few decades. Otherwise nature will have

licked its wounds and recovered its devastation. Soon the

land will again be covered with spruce, cedar and alder, and all

signs except the gigantic crater will have vanished.

*** THE END ***