The Warther Museum

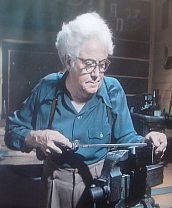

Ernest "Mooney" Warther

Dover, OH

July 7th, 2005

As  we

travel back and forth across North America, we are always on the alert of

something new and interesting. Sometimes we simply drive up on it, quite surprised,

and on other times it is the work of long distant plans which have been on hold

for months, if not years. So it was, while sitting around a picnic table

in central Florida, one day last winter, that we first heard about the fantastic

carvings of Ernest Warther. Having carved most of my life, I was

immediately interested in the story. Soooo, as we passed through Ohio, en

route to New England for the summer, we plotted our course through the small

community of Dover, less than 100 miles northeast of Columbus, Ohio. Ernest

"Mooney" Warther was born in Dover, Ohio, on October 30, 1885.

His parents, who had immigrated from Switzerland, were of modest means.

we

travel back and forth across North America, we are always on the alert of

something new and interesting. Sometimes we simply drive up on it, quite surprised,

and on other times it is the work of long distant plans which have been on hold

for months, if not years. So it was, while sitting around a picnic table

in central Florida, one day last winter, that we first heard about the fantastic

carvings of Ernest Warther. Having carved most of my life, I was

immediately interested in the story. Soooo, as we passed through Ohio, en

route to New England for the summer, we plotted our course through the small

community of Dover, less than 100 miles northeast of Columbus, Ohio. Ernest

"Mooney" Warther was born in Dover, Ohio, on October 30, 1885.

His parents, who had immigrated from Switzerland, were of modest means.  When

Ernest's father died, Ernest was only three. His mother had to get by the

best she could, by taking in wash and boarders. Ernest only attended

school to the second grade, as every effort was required just to keep food on the

table. In the late 1800s, most of the towns folks owned a cow or two for

milking. Ernest spent most of his time walking the cows from town to the

pastures on surrounding farms, and then back again in the evenings. It was this endeavor

that earned Ernest his long lasting nickname of "Mooney", which is

Swiss for "Bull of the Herd". So the story goes, Mooney was

walking the cows one day when he found an old penknife laying on the road.

With many hours to spare waiting for the cows, he soon began to create rustic

carvings. One day a passing hobo carved a pair of wooden pliers for

him. Mooney was fascinated and took the toy

When

Ernest's father died, Ernest was only three. His mother had to get by the

best she could, by taking in wash and boarders. Ernest only attended

school to the second grade, as every effort was required just to keep food on the

table. In the late 1800s, most of the towns folks owned a cow or two for

milking. Ernest spent most of his time walking the cows from town to the

pastures on surrounding farms, and then back again in the evenings. It was this endeavor

that earned Ernest his long lasting nickname of "Mooney", which is

Swiss for "Bull of the Herd". So the story goes, Mooney was

walking the cows one day when he found an old penknife laying on the road.

With many hours to spare waiting for the cows, he soon began to create rustic

carvings. One day a passing hobo carved a pair of wooden pliers for

him. Mooney was fascinated and took the toy  home

to study it. Soon he was producing carved pliers and over time it became

his trademark. One estimate holds that he carved over 3/4 of a million pliers

in his lifetime. As we arrived at the museum, we were invited into a small

auditorium where we met the grandson, who after giving a short opening

statement, whipped out his own now famous multi-blade pocket carving knife and in just

seconds converted a small squared stick of soft wood into one of the trademark

pliers. I never had an opportunity to examine the pliers as he handed it

to a small girl who ran off. There are only about 10 cuts to the

design. To make it more interesting, Mooney would carve each handle of the

pliers into another pair of pliers. He continued this until he created a

masterpiece. From a large solid block of wood he carved a large pair of

pliers, then carved the handles, then carved those handles into more pliers.

He continued this for some 31 thousand cuts or until he had created 511 pliers,

all connected. He built this into a round carved display wheel where it

sits today. The design is such that when all pliers are folded up, they

return to a solid block of wood.

home

to study it. Soon he was producing carved pliers and over time it became

his trademark. One estimate holds that he carved over 3/4 of a million pliers

in his lifetime. As we arrived at the museum, we were invited into a small

auditorium where we met the grandson, who after giving a short opening

statement, whipped out his own now famous multi-blade pocket carving knife and in just

seconds converted a small squared stick of soft wood into one of the trademark

pliers. I never had an opportunity to examine the pliers as he handed it

to a small girl who ran off. There are only about 10 cuts to the

design. To make it more interesting, Mooney would carve each handle of the

pliers into another pair of pliers. He continued this until he created a

masterpiece. From a large solid block of wood he carved a large pair of

pliers, then carved the handles, then carved those handles into more pliers.

He continued this for some 31 thousand cuts or until he had created 511 pliers,

all connected. He built this into a round carved display wheel where it

sits today. The design is such that when all pliers are folded up, they

return to a solid block of wood.  By age 14, Mooney was old enough

to join the work force proper and so he went to work as a scrap bundler in a

local mill. He worked there for 23 years until his real calling took over his

life. At 28 he was prepared to take the next step in his carving

adventure. He build a very modest workshop, and by his own additions, quit

the whittling business to get down to serious carving. The workshop

is now attached to the museum. Within this small workshop Mooney saw his

other true love merge with his love of carving. From the first day, he

began a life long labor to re-create in miniature, the locomotives that he so

admired. When seen in their entirety, the train carvings span the

evolution of the steam engine in sixty-four carvings starting with the Hero

Engine of circa 250 BC to the

By age 14, Mooney was old enough

to join the work force proper and so he went to work as a scrap bundler in a

local mill. He worked there for 23 years until his real calling took over his

life. At 28 he was prepared to take the next step in his carving

adventure. He build a very modest workshop, and by his own additions, quit

the whittling business to get down to serious carving. The workshop

is now attached to the museum. Within this small workshop Mooney saw his

other true love merge with his love of carving. From the first day, he

began a life long labor to re-create in miniature, the locomotives that he so

admired. When seen in their entirety, the train carvings span the

evolution of the steam engine in sixty-four carvings starting with the Hero

Engine of circa 250 BC to the Union Pacific Big

Boy Locomotive of 1941. During

the 23 years at the steel plant Mooney learned to forge and temper steel from

a neighborhood blacksmith. He put this knowledge to work when he became

discouraged with the carving knives he had been using. They just weren't

right. Soon he was doing detailed carvings with specialized blades of his

own design. So the story goes, his mother's complaint about a dull kitchen

knife started a new adventure in his life. The small paring knife he made

for her soon became the talk of the sewing circles and the requests for knives

rolled in. When the mill closed down for a while, Mooney launched

himself into creating a set of kitchen knives for sale. This was the

beginning of the Warther Kitchen Cutlery business which is still running

today. Armed with specialized knives made of the highest quality steels,

Mooney was able to create models that most carvers only dream about. His

approach was one of absolute dedication to accuracy. To this extent, he

would carve the parts of a train separately then attach them properly to the

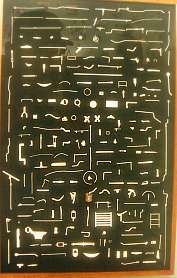

carved body. He used ivory and ebony to make stark contrasts. One

board on a wall contained all the small intricate parts that he was required to

make. That is far more dedication that I'll ever have.

Union Pacific Big

Boy Locomotive of 1941. During

the 23 years at the steel plant Mooney learned to forge and temper steel from

a neighborhood blacksmith. He put this knowledge to work when he became

discouraged with the carving knives he had been using. They just weren't

right. Soon he was doing detailed carvings with specialized blades of his

own design. So the story goes, his mother's complaint about a dull kitchen

knife started a new adventure in his life. The small paring knife he made

for her soon became the talk of the sewing circles and the requests for knives

rolled in. When the mill closed down for a while, Mooney launched

himself into creating a set of kitchen knives for sale. This was the

beginning of the Warther Kitchen Cutlery business which is still running

today. Armed with specialized knives made of the highest quality steels,

Mooney was able to create models that most carvers only dream about. His

approach was one of absolute dedication to accuracy. To this extent, he

would carve the parts of a train separately then attach them properly to the

carved body. He used ivory and ebony to make stark contrasts. One

board on a wall contained all the small intricate parts that he was required to

make. That is far more dedication that I'll ever have.  After 23 years at the steel plant and some 25 locomotives on

display at his house, Mooney enjoyed quite a name for himself as a

first class detail carver unrivaled at the time. When the New

York Central Railroad heard about Mooney's carvings, they talked him into

quitting his job at the mill and going on tour for the Railroad for 6 months

after which he was to go to Grand Central Station in New York for another 2 1/2

years with his creations where he would talk about carving and make souvenir

wooden pliers. When his contract was up, the Railroad offered him a

whopping 50 thousand dollars for his collection. When Henry Ford heard

about the offer he increased the amount but Mooney, who considered himself a

simple man, turned them all down, returning with his treasures to the home where

it all started. Upon arriving home, he decided not to return to the steel mill.

Instead he started the knife shop back up again, and began charging a small

admission to see his carvings at shows. He continued this through the

great depression of '29 until he built a small building to display his

works. The carvings remained there until 1963 when his son built a large

building which houses the museum today. World War II found him with mixed

feelings.

After 23 years at the steel plant and some 25 locomotives on

display at his house, Mooney enjoyed quite a name for himself as a

first class detail carver unrivaled at the time. When the New

York Central Railroad heard about Mooney's carvings, they talked him into

quitting his job at the mill and going on tour for the Railroad for 6 months

after which he was to go to Grand Central Station in New York for another 2 1/2

years with his creations where he would talk about carving and make souvenir

wooden pliers. When his contract was up, the Railroad offered him a

whopping 50 thousand dollars for his collection. When Henry Ford heard

about the offer he increased the amount but Mooney, who considered himself a

simple man, turned them all down, returning with his treasures to the home where

it all started. Upon arriving home, he decided not to return to the steel mill.

Instead he started the knife shop back up again, and began charging a small

admission to see his carvings at shows. He continued this through the

great depression of '29 until he built a small building to display his

works. The carvings remained there until 1963 when his son built a large

building which houses the museum today. World War II found him with mixed

feelings.  He hated the idea of war but wanted to support the men. He

once again turned to his small machine shop to make what he knew best.

Over the next 4 years he produced approximately 1100 hand forged commando knifes

for those who asked for them. Each one was made specifically for an individual

service man, complete with the man's name stamped into a brass plate in the

cocobolo handle. Today they are considered prized possessions by those who

have hung onto them. It is said that he was grinding out yet another

commando knife when word reached him from town that the war had ended. He put

the knife down and never finished it or any other. The last commando knife

is now on display in the museum.

He hated the idea of war but wanted to support the men. He

once again turned to his small machine shop to make what he knew best.

Over the next 4 years he produced approximately 1100 hand forged commando knifes

for those who asked for them. Each one was made specifically for an individual

service man, complete with the man's name stamped into a brass plate in the

cocobolo handle. Today they are considered prized possessions by those who

have hung onto them. It is said that he was grinding out yet another

commando knife when word reached him from town that the war had ended. He put

the knife down and never finished it or any other. The last commando knife

is now on display in the museum.  Mooney continued his love

of locomotives, carving each and every one with such care that it was hard to

believe that they had been created with an edged blade. Most were created

by making the parts such as wheels and rods and then hooking them up to make a perfect

moving train. In 1953 at the age of 68, he realized that the dreaded Diesel

powered train had arrived and the age of steam was passing by. He was

determined to never carve a diesel and so turned his attention into yet another

direction. At the age of 72 he picked up his knife again and began what he

called the "Great Events in American Railroad History". These diorama-like complex creations are masterpieces of events in history which were

significant to Mooney. By age 80 he was back to his first love.

Trains. One of his most endearing creations is the Lincoln funeral train,

in ebony and ivory with mother of pearl. He was still carving at 87 when

he died leaving an unfinished work sitting on the workbench. This is a great place

to see something out of the way and different and for train buffs and carvers

this is an absolute must,

Mooney continued his love

of locomotives, carving each and every one with such care that it was hard to

believe that they had been created with an edged blade. Most were created

by making the parts such as wheels and rods and then hooking them up to make a perfect

moving train. In 1953 at the age of 68, he realized that the dreaded Diesel

powered train had arrived and the age of steam was passing by. He was

determined to never carve a diesel and so turned his attention into yet another

direction. At the age of 72 he picked up his knife again and began what he

called the "Great Events in American Railroad History". These diorama-like complex creations are masterpieces of events in history which were

significant to Mooney. By age 80 he was back to his first love.

Trains. One of his most endearing creations is the Lincoln funeral train,

in ebony and ivory with mother of pearl. He was still carving at 87 when

he died leaving an unfinished work sitting on the workbench. This is a great place

to see something out of the way and different and for train buffs and carvers

this is an absolute must,

***THE END ***