took

us to pass through our smallest state was far too short to find all the things

that were part of this land. We did find an interesting

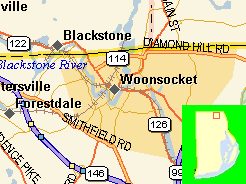

town up on the northern border with Massachusetts. Here the Blackstone

River runs relentlessly to the sea. And it was the Blackstone that brought prosperity

and a new way of life for many foreigners seeking to better themselves in the

bright new land. The 1600s saw this part of the country still under the control

of the local Indians, but that changed in 1660 when Richard Arnold

constructed the first sawmill on the Blackstone River. Success breeds imitation

and shortly thereafter Arnold's friends, relatives and other enthusiastic colonists

migrated to the area and set up similar operations. With this, came the necessity

of other trades and business and soon there were 6 small villages along the

banks of the river. Trade grew steadily with the river always providing

ample power for the mills. With the 1800s

took

us to pass through our smallest state was far too short to find all the things

that were part of this land. We did find an interesting

town up on the northern border with Massachusetts. Here the Blackstone

River runs relentlessly to the sea. And it was the Blackstone that brought prosperity

and a new way of life for many foreigners seeking to better themselves in the

bright new land. The 1600s saw this part of the country still under the control

of the local Indians, but that changed in 1660 when Richard Arnold

constructed the first sawmill on the Blackstone River. Success breeds imitation

and shortly thereafter Arnold's friends, relatives and other enthusiastic colonists

migrated to the area and set up similar operations. With this, came the necessity

of other trades and business and soon there were 6 small villages along the

banks of the river. Trade grew steadily with the river always providing

ample power for the mills. With the 1800s  came

an explosion in the area. Textiles had advanced in technology to allow

for large labor-intensive mills which required great power to run the massive

drive belts that pumped the hundred of looms throughout the mills. Again, the

Blackstone River supplied the never-ending power needed. The growth saw

the 6 small villages come together to form the town of Woonsocket. The beginning

of the 1900s saw Woonsocket at its heyday. During this time a ready made

labor force came down from Quebec to work the looms. These were hard times

for those who arrived. Much of the City's rich history is in the struggles

of these immigrants in a new land. The mills are all gone now, as is much

of the culture, but a small part of it is preserved in a museum in the middle of

the town. We dropped by to see what we could learn about the past and we

certainly found that. Inside we found the story of a world in change. Not only

was the industry brand new,

came

an explosion in the area. Textiles had advanced in technology to allow

for large labor-intensive mills which required great power to run the massive

drive belts that pumped the hundred of looms throughout the mills. Again, the

Blackstone River supplied the never-ending power needed. The growth saw

the 6 small villages come together to form the town of Woonsocket. The beginning

of the 1900s saw Woonsocket at its heyday. During this time a ready made

labor force came down from Quebec to work the looms. These were hard times

for those who arrived. Much of the City's rich history is in the struggles

of these immigrants in a new land. The mills are all gone now, as is much

of the culture, but a small part of it is preserved in a museum in the middle of

the town. We dropped by to see what we could learn about the past and we

certainly found that. Inside we found the story of a world in change. Not only

was the industry brand new,  the

workers were also new. Many of them came from the poor farmlands of Quebec

and didn't speak English. There were no rules in the factory to start

with. It was take or leave it job opportunity. Initially, the immigrants fell

into 4 categories. There were the unskilled laborers, fresh off the

farms. These people found work on the canals and building roads which were

expanding to carry away the goods, the factories were turning out. The

skilled workers or artisans, whose jobs soon disappeared when machines were made

to replace them, found themselves forced into the factory labor force. The

outworkers were those, mostly wives and mothers, who worked at cottage industries

in their homes. Many of the items they made were on display in the museum. This

was never a viable source of income as most of the items were labor intensive

and were sold individually for whatever the maker could get. The final

group was the children. In the early 1800s there were no child labor laws

and many families found it necessary to send their children to the factories

rather then school. With little body strength and no skills, the children got

the most mundane repetitive jobs which demanded that they act swiftly and accurately

if they had any hope of keeping their jobs. One of the jobs given to such

workers was to load the spindles

the

workers were also new. Many of them came from the poor farmlands of Quebec

and didn't speak English. There were no rules in the factory to start

with. It was take or leave it job opportunity. Initially, the immigrants fell

into 4 categories. There were the unskilled laborers, fresh off the

farms. These people found work on the canals and building roads which were

expanding to carry away the goods, the factories were turning out. The

skilled workers or artisans, whose jobs soon disappeared when machines were made

to replace them, found themselves forced into the factory labor force. The

outworkers were those, mostly wives and mothers, who worked at cottage industries

in their homes. Many of the items they made were on display in the museum. This

was never a viable source of income as most of the items were labor intensive

and were sold individually for whatever the maker could get. The final

group was the children. In the early 1800s there were no child labor laws

and many families found it necessary to send their children to the factories

rather then school. With little body strength and no skills, the children got

the most mundane repetitive jobs which demanded that they act swiftly and accurately

if they had any hope of keeping their jobs. One of the jobs given to such

workers was to load the spindles onto the spindle board. It took very little capital to build a textile

mill and soon competition was eating up profits. The factories developed a

solution called "speed up and stretch out" which meant that

factories began requiring more product to be produced per hour and longer hours for

the same amount of pay. This caused an increase in injuries and a general

unhappiness of the workers, but the factories were uninterested in these

conditions. Soon job actions began to spring up. Some skilled

workers unionized, others staged walkouts, and the poorest of them all simply

packed up and went home, when conditions got too bad. This had no effect on

the factories who were actively recruiting new immigrants to fill

their positions. The struggle did not end at the workplace. These

immigrants found themselves transplanted into an English speaking country with

different culture and values and religion. Many of the French workers did assimilate,

giving up their French ways for the new life in America. Many others

fought off this assimilation, and fought for their language and culture and

religion. The expression "la survivance" became the common term

for holding on to the French in their past. Even today one can find, among

the old folks around town, evidence of the old "la survivance". A tapestry sent

from Paris in 1920 and which hung in the Our Lady of Victories Church is an

example of the continued attachment to the homeland and the way it use to

be.

onto the spindle board. It took very little capital to build a textile

mill and soon competition was eating up profits. The factories developed a

solution called "speed up and stretch out" which meant that

factories began requiring more product to be produced per hour and longer hours for

the same amount of pay. This caused an increase in injuries and a general

unhappiness of the workers, but the factories were uninterested in these

conditions. Soon job actions began to spring up. Some skilled

workers unionized, others staged walkouts, and the poorest of them all simply

packed up and went home, when conditions got too bad. This had no effect on

the factories who were actively recruiting new immigrants to fill

their positions. The struggle did not end at the workplace. These

immigrants found themselves transplanted into an English speaking country with

different culture and values and religion. Many of the French workers did assimilate,

giving up their French ways for the new life in America. Many others

fought off this assimilation, and fought for their language and culture and

religion. The expression "la survivance" became the common term

for holding on to the French in their past. Even today one can find, among

the old folks around town, evidence of the old "la survivance". A tapestry sent

from Paris in 1920 and which hung in the Our Lady of Victories Church is an

example of the continued attachment to the homeland and the way it use to

be. There were other things to do in town, including some old mill tours and historical walks, and of course there is the ever constant Blackstone River with all its beauty running through all of it.