Old Fort William

Center of

the Fur Trade

Thunder Bay,

Ontario

June 26th,, 2000

My  specialty

in writing about our travels has been history museums. Over the

years we have seen our share. I tend to break them into three

types, not necessarily recognized by any museum authority. There

are the static museums, or artifact storage centers. Filled with

glass cases displaying those items deemed too fragile to be

handled. Of more interest to me are those who present their

artifacts in dioramic settings. The settings can be anywhere from

small carved wooden figures on a small stage to full sized

animatronic figures using such artifacts to their intended

purpose. Then there is my favorite, the living museum, which

presents history as nearly as possible to the life and times of

the period represented. So when I heard that Fort William was a

living museum, I was ready to go. Our first step was to contact

Marty Mascarin, the Fort's communications officer and set up the

shoot. Marty couldn't have been more helpful, as he arranged all

that was necessary to record the story. Upon our arrival, we

found the visitor's center to be impressive with its massive

tamarack columns supporting the welcome shelter at the entrance.

Opposite the front door, is a large mural covering the entire

wall, depicting the fur trade which was the cause of all this

historical activity. Fort

specialty

in writing about our travels has been history museums. Over the

years we have seen our share. I tend to break them into three

types, not necessarily recognized by any museum authority. There

are the static museums, or artifact storage centers. Filled with

glass cases displaying those items deemed too fragile to be

handled. Of more interest to me are those who present their

artifacts in dioramic settings. The settings can be anywhere from

small carved wooden figures on a small stage to full sized

animatronic figures using such artifacts to their intended

purpose. Then there is my favorite, the living museum, which

presents history as nearly as possible to the life and times of

the period represented. So when I heard that Fort William was a

living museum, I was ready to go. Our first step was to contact

Marty Mascarin, the Fort's communications officer and set up the

shoot. Marty couldn't have been more helpful, as he arranged all

that was necessary to record the story. Upon our arrival, we

found the visitor's center to be impressive with its massive

tamarack columns supporting the welcome shelter at the entrance.

Opposite the front door, is a large mural covering the entire

wall, depicting the fur trade which was the cause of all this

historical activity. Fort  William is a misnomer in that it was never

actually a fort, and never housed military troops. It was, for

the most part, a trading post and collection point of the North

West Company, a British business and one of the chief rivals of

the Hudson Bay Company. The North West Company was finally merged

with Hudson Bay, making the latter the largest trading company in

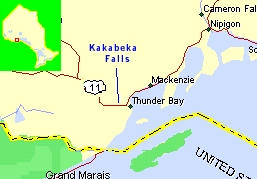

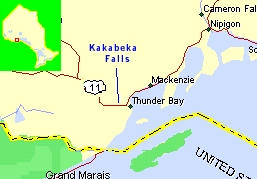

the North. It got its start when the 49th parallel was

established as the boundary between the U.S. and Canada. This put

the North West trading center at Grand Portage in Minnesota, and

as the U.S. began to exert excise taxes on the furs, the North

West Company moved

William is a misnomer in that it was never

actually a fort, and never housed military troops. It was, for

the most part, a trading post and collection point of the North

West Company, a British business and one of the chief rivals of

the Hudson Bay Company. The North West Company was finally merged

with Hudson Bay, making the latter the largest trading company in

the North. It got its start when the 49th parallel was

established as the boundary between the U.S. and Canada. This put

the North West trading center at Grand Portage in Minnesota, and

as the U.S. began to exert excise taxes on the furs, the North

West Company moved  their center of collection north to Thunder Bay,

just over the border. There is a short but well done film on the

trading post's activities during its heyday in the mid 1800s.

and of course there is a prime example of the cause that created

a need for such a large trading post in such a wilderness, that

ever fashionable, always desired fur felt top hat. With the

winter months freezing the rivers, transportation from the far

west to Montreal oftentimes took more then one season. In order

to facilitate this movement, a collection and trading point was

needed mid-way. Transportation was broken up into two parts.

Those who brought trading goods from Montreal to the Fort and

took furs back; and those who brought furs from the west and took

trading goods back. The North West

their center of collection north to Thunder Bay,

just over the border. There is a short but well done film on the

trading post's activities during its heyday in the mid 1800s.

and of course there is a prime example of the cause that created

a need for such a large trading post in such a wilderness, that

ever fashionable, always desired fur felt top hat. With the

winter months freezing the rivers, transportation from the far

west to Montreal oftentimes took more then one season. In order

to facilitate this movement, a collection and trading point was

needed mid-way. Transportation was broken up into two parts.

Those who brought trading goods from Montreal to the Fort and

took furs back; and those who brought furs from the west and took

trading goods back. The North West  company had no desire to create a settlement out

of the Fort so non-essential people were not allowed. This

included European women and children. The Fort was strictly

business and, as such, had set up a rigid class distinction. This

was enforced by a tall palisade surrounding the main buildings

for which access was denied to many. As we passed through the

visitors center and out onto the staircase in the rear we were

offered to walk or ride to the fort, several hundred yards away.

We elected to walk, reading the placards along the way. We

arrived at the collection point shortly there after and waited

while the group grew in size sufficient to have a guide. During

this time we got a basic overview

company had no desire to create a settlement out

of the Fort so non-essential people were not allowed. This

included European women and children. The Fort was strictly

business and, as such, had set up a rigid class distinction. This

was enforced by a tall palisade surrounding the main buildings

for which access was denied to many. As we passed through the

visitors center and out onto the staircase in the rear we were

offered to walk or ride to the fort, several hundred yards away.

We elected to walk, reading the placards along the way. We

arrived at the collection point shortly there after and waited

while the group grew in size sufficient to have a guide. During

this time we got a basic overview  of the park. Built as an authentic duplicate of

its namesake, by the Canadian government, this 25 acre site

contains 42 re-created historic buildings, staffed with actors

portraying the Fort and its operations during the early 1800s.

With sufficient people gathered, we moved on to our first visit

which was with the Ojibwa (Chipewa)Indians, camped along the

Kaministiquia River. Here we met 17 year old Hiim-Anong (dancing

star). The Ojibwas were the bottom rung of the entire North West

Company operation, as they supplied not only the precious pelts

for the top hats of the elite of Europe, but much of the raw

material needed to exist in this wilderness; canoes, snowshoes,

and moccasins, along with supplies of meat from wild game were

all trade items for the Indians. There were several wigwams, both

summer and winter, complete with traditional household items.

of the park. Built as an authentic duplicate of

its namesake, by the Canadian government, this 25 acre site

contains 42 re-created historic buildings, staffed with actors

portraying the Fort and its operations during the early 1800s.

With sufficient people gathered, we moved on to our first visit

which was with the Ojibwa (Chipewa)Indians, camped along the

Kaministiquia River. Here we met 17 year old Hiim-Anong (dancing

star). The Ojibwas were the bottom rung of the entire North West

Company operation, as they supplied not only the precious pelts

for the top hats of the elite of Europe, but much of the raw

material needed to exist in this wilderness; canoes, snowshoes,

and moccasins, along with supplies of meat from wild game were

all trade items for the Indians. There were several wigwams, both

summer and winter, complete with traditional household items.

<<<<< Back

Next

>>>>>

<<<<< Back

Next

>>>>>

specialty

in writing about our travels has been history museums. Over the

years we have seen our share. I tend to break them into three

types, not necessarily recognized by any museum authority. There

are the static museums, or artifact storage centers. Filled with

glass cases displaying those items deemed too fragile to be

handled. Of more interest to me are those who present their

artifacts in dioramic settings. The settings can be anywhere from

small carved wooden figures on a small stage to full sized

animatronic figures using such artifacts to their intended

purpose. Then there is my favorite, the living museum, which

presents history as nearly as possible to the life and times of

the period represented. So when I heard that Fort William was a

living museum, I was ready to go. Our first step was to contact

Marty Mascarin, the Fort's communications officer and set up the

shoot. Marty couldn't have been more helpful, as he arranged all

that was necessary to record the story. Upon our arrival, we

found the visitor's center to be impressive with its massive

tamarack columns supporting the welcome shelter at the entrance.

Opposite the front door, is a large mural covering the entire

wall, depicting the fur trade which was the cause of all this

historical activity. Fort

specialty

in writing about our travels has been history museums. Over the

years we have seen our share. I tend to break them into three

types, not necessarily recognized by any museum authority. There

are the static museums, or artifact storage centers. Filled with

glass cases displaying those items deemed too fragile to be

handled. Of more interest to me are those who present their

artifacts in dioramic settings. The settings can be anywhere from

small carved wooden figures on a small stage to full sized

animatronic figures using such artifacts to their intended

purpose. Then there is my favorite, the living museum, which

presents history as nearly as possible to the life and times of

the period represented. So when I heard that Fort William was a

living museum, I was ready to go. Our first step was to contact

Marty Mascarin, the Fort's communications officer and set up the

shoot. Marty couldn't have been more helpful, as he arranged all

that was necessary to record the story. Upon our arrival, we

found the visitor's center to be impressive with its massive

tamarack columns supporting the welcome shelter at the entrance.

Opposite the front door, is a large mural covering the entire

wall, depicting the fur trade which was the cause of all this

historical activity. Fort  William is a misnomer in that it was never

actually a fort, and never housed military troops. It was, for

the most part, a trading post and collection point of the North

West Company, a British business and one of the chief rivals of

the Hudson Bay Company. The North West Company was finally merged

with Hudson Bay, making the latter the largest trading company in

the North. It got its start when the 49th parallel was

established as the boundary between the U.S. and Canada. This put

the North West trading center at Grand Portage in Minnesota, and

as the U.S. began to exert excise taxes on the furs, the North

West Company moved

William is a misnomer in that it was never

actually a fort, and never housed military troops. It was, for

the most part, a trading post and collection point of the North

West Company, a British business and one of the chief rivals of

the Hudson Bay Company. The North West Company was finally merged

with Hudson Bay, making the latter the largest trading company in

the North. It got its start when the 49th parallel was

established as the boundary between the U.S. and Canada. This put

the North West trading center at Grand Portage in Minnesota, and

as the U.S. began to exert excise taxes on the furs, the North

West Company moved  their center of collection north to Thunder Bay,

just over the border. There is a short but well done film on the

trading post's activities during its heyday in the mid 1800s.

and of course there is a prime example of the cause that created

a need for such a large trading post in such a wilderness, that

ever fashionable, always desired fur felt top hat. With the

winter months freezing the rivers, transportation from the far

west to Montreal oftentimes took more then one season. In order

to facilitate this movement, a collection and trading point was

needed mid-way. Transportation was broken up into two parts.

Those who brought trading goods from Montreal to the Fort and

took furs back; and those who brought furs from the west and took

trading goods back. The North West

their center of collection north to Thunder Bay,

just over the border. There is a short but well done film on the

trading post's activities during its heyday in the mid 1800s.

and of course there is a prime example of the cause that created

a need for such a large trading post in such a wilderness, that

ever fashionable, always desired fur felt top hat. With the

winter months freezing the rivers, transportation from the far

west to Montreal oftentimes took more then one season. In order

to facilitate this movement, a collection and trading point was

needed mid-way. Transportation was broken up into two parts.

Those who brought trading goods from Montreal to the Fort and

took furs back; and those who brought furs from the west and took

trading goods back. The North West  company had no desire to create a settlement out

of the Fort so non-essential people were not allowed. This

included European women and children. The Fort was strictly

business and, as such, had set up a rigid class distinction. This

was enforced by a tall palisade surrounding the main buildings

for which access was denied to many. As we passed through the

visitors center and out onto the staircase in the rear we were

offered to walk or ride to the fort, several hundred yards away.

We elected to walk, reading the placards along the way. We

arrived at the collection point shortly there after and waited

while the group grew in size sufficient to have a guide. During

this time we got a basic overview

company had no desire to create a settlement out

of the Fort so non-essential people were not allowed. This

included European women and children. The Fort was strictly

business and, as such, had set up a rigid class distinction. This

was enforced by a tall palisade surrounding the main buildings

for which access was denied to many. As we passed through the

visitors center and out onto the staircase in the rear we were

offered to walk or ride to the fort, several hundred yards away.

We elected to walk, reading the placards along the way. We

arrived at the collection point shortly there after and waited

while the group grew in size sufficient to have a guide. During

this time we got a basic overview  of the park. Built as an authentic duplicate of

its namesake, by the Canadian government, this 25 acre site

contains 42 re-created historic buildings, staffed with actors

portraying the Fort and its operations during the early 1800s.

With sufficient people gathered, we moved on to our first visit

which was with the Ojibwa (Chipewa)Indians, camped along the

Kaministiquia River. Here we met 17 year old Hiim-Anong (dancing

star). The Ojibwas were the bottom rung of the entire North West

Company operation, as they supplied not only the precious pelts

for the top hats of the elite of Europe, but much of the raw

material needed to exist in this wilderness; canoes, snowshoes,

and moccasins, along with supplies of meat from wild game were

all trade items for the Indians. There were several wigwams, both

summer and winter, complete with traditional household items.

of the park. Built as an authentic duplicate of

its namesake, by the Canadian government, this 25 acre site

contains 42 re-created historic buildings, staffed with actors

portraying the Fort and its operations during the early 1800s.

With sufficient people gathered, we moved on to our first visit

which was with the Ojibwa (Chipewa)Indians, camped along the

Kaministiquia River. Here we met 17 year old Hiim-Anong (dancing

star). The Ojibwas were the bottom rung of the entire North West

Company operation, as they supplied not only the precious pelts

for the top hats of the elite of Europe, but much of the raw

material needed to exist in this wilderness; canoes, snowshoes,

and moccasins, along with supplies of meat from wild game were

all trade items for the Indians. There were several wigwams, both

summer and winter, complete with traditional household items.  <<<<< Back

Next

>>>>>

<<<<< Back

Next

>>>>>