From here we wandered

along the front of the palisade to the entrance. The outside

perimeter of the Fort was the home of the Voyagers. These mostly

French-Canadians worked as paddlers on the hundreds of canoes

that plied the waters both east and west carrying supplies and

fur to their respective destinations. They were broken into two

separate groups. The "Winterers" who traded with the

Indians in the west during the winter and then brought the furs

they received out of the west by canoe until they reached  Fort

William. They would then take trade goods back west to exchange

for more furs. The other group known as the "pork

eaters" were usually much bigger in size and quite

physically strong. They would pack the 90 lb. fur packs into

canoes and paddle them east to Montreal, and bring back trade

goods. There were many points at which the fur packs had to be

portaged around bad water and falls. Each man was expected to

carry a minimum of 2 packs, and many carried three. During the

great rendezvous in mid-summer, when the voyageurs from the west

and the voyagers from the east both arrived at the at the same

time, there might be several thousand people at the Fort. During

the cold winter months when there was

Fort

William. They would then take trade goods back west to exchange

for more furs. The other group known as the "pork

eaters" were usually much bigger in size and quite

physically strong. They would pack the 90 lb. fur packs into

canoes and paddle them east to Montreal, and bring back trade

goods. There were many points at which the fur packs had to be

portaged around bad water and falls. Each man was expected to

carry a minimum of 2 packs, and many carried three. During the

great rendezvous in mid-summer, when the voyageurs from the west

and the voyagers from the east both arrived at the at the same

time, there might be several thousand people at the Fort. During

the cold winter months when there was little or no activity, there might not be more

the 40 people at the fort. To feed the large gathering during the

summer months, extensive farming was conducted in and around the

Fort. Horses, cattle, sheep, chickens, a large vegetable garden

and an assortment of animal fodder were needed. This all required

buildings. Barns, houses, a great dining hall, store rooms, and a

power magazine. Carpenters, brick layers, and coopers were hired.

Then there were the clerks, accountants and stockmen responsible

for keeping track of the trade goods and getting the furs ready

for shipment east. On top of this was a small group of mostly

Scottish men who managed the entire operation for the Montreal

owners. Although located deep in the wilderness, Fort William was

not lacking for

little or no activity, there might not be more

the 40 people at the fort. To feed the large gathering during the

summer months, extensive farming was conducted in and around the

Fort. Horses, cattle, sheep, chickens, a large vegetable garden

and an assortment of animal fodder were needed. This all required

buildings. Barns, houses, a great dining hall, store rooms, and a

power magazine. Carpenters, brick layers, and coopers were hired.

Then there were the clerks, accountants and stockmen responsible

for keeping track of the trade goods and getting the furs ready

for shipment east. On top of this was a small group of mostly

Scottish men who managed the entire operation for the Montreal

owners. Although located deep in the wilderness, Fort William was

not lacking for amenities. Many types of craftsmen made their

living. plying their trade within the palisade walls. In addition

aristocratic visitors often arrived to review the business for an

extended period of time. As we rounded the corner into the fort

we came upon several buildings, each with its own actors. The

schooner Captain, the Doctor, each with a story to tell. With

accents practiced, they would enter into lively conversations

with both other actors or any of the visitors who happed to ask a

question. Always quick to act confused when anything prior to

their period was mentioned, such as computers, airplanes,

telephones, or cars, these

amenities. Many types of craftsmen made their

living. plying their trade within the palisade walls. In addition

aristocratic visitors often arrived to review the business for an

extended period of time. As we rounded the corner into the fort

we came upon several buildings, each with its own actors. The

schooner Captain, the Doctor, each with a story to tell. With

accents practiced, they would enter into lively conversations

with both other actors or any of the visitors who happed to ask a

question. Always quick to act confused when anything prior to

their period was mentioned, such as computers, airplanes,

telephones, or cars, these  docents presented a perfect image of the time

they so richly presented. As we entered the trading floor, we

were greeted with an assortment of dry goods, hardware, knives

and muskets, all arranged neatly on shelves. Each had a price, so

many plus (pronounced plew). A plus equals a credit which is paid

for by one beaver pelt, with some ability to slide the value one

way or another. Gold, silver or currency were not used in the

Fort. The basic unit of payment was one beaver skin. From the

docents presented a perfect image of the time

they so richly presented. As we entered the trading floor, we

were greeted with an assortment of dry goods, hardware, knives

and muskets, all arranged neatly on shelves. Each had a price, so

many plus (pronounced plew). A plus equals a credit which is paid

for by one beaver pelt, with some ability to slide the value one

way or another. Gold, silver or currency were not used in the

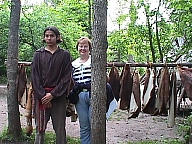

Fort. The basic unit of payment was one beaver skin. From the  trading

floor, we moved to the fur packing storehouse. Here, hanging form

the rafters and on poles throughout the entire warehouse were

pelts of every description, from beaver to arctic fox. These were

the real thing, actually captured from poachers over the years

and lent to the museum by the authorities. In the middle of the

room was a fur press. Beaver skins were compressed until a pile

of them weighed 90 lbs. They were then wrapped and tied and

became a basic fur pack which the voyagers had to carry. A young

man demonstrated the required strength as he showed how two packs

were carried using a head strap. With a mighty heave he stood

straight up under 180 lbs of beaver fur and staggered around the

room for a complete circle. The strain on his body was enormous

and evident by the protruding veins in his neck. An offer for

others in the room to try the back pack fully loaded was not

accepted by anyone.

trading

floor, we moved to the fur packing storehouse. Here, hanging form

the rafters and on poles throughout the entire warehouse were

pelts of every description, from beaver to arctic fox. These were

the real thing, actually captured from poachers over the years

and lent to the museum by the authorities. In the middle of the

room was a fur press. Beaver skins were compressed until a pile

of them weighed 90 lbs. They were then wrapped and tied and

became a basic fur pack which the voyagers had to carry. A young

man demonstrated the required strength as he showed how two packs

were carried using a head strap. With a mighty heave he stood

straight up under 180 lbs of beaver fur and staggered around the

room for a complete circle. The strain on his body was enormous

and evident by the protruding veins in his neck. An offer for

others in the room to try the back pack fully loaded was not

accepted by anyone.

<<<<<

Back

Next >>>>>

<<<<<

Back

Next >>>>>

Fort

William. They would then take trade goods back west to exchange

for more furs. The other group known as the "pork

eaters" were usually much bigger in size and quite

physically strong. They would pack the 90 lb. fur packs into

canoes and paddle them east to Montreal, and bring back trade

goods. There were many points at which the fur packs had to be

portaged around bad water and falls. Each man was expected to

carry a minimum of 2 packs, and many carried three. During the

great rendezvous in mid-summer, when the voyageurs from the west

and the voyagers from the east both arrived at the at the same

time, there might be several thousand people at the Fort. During

the cold winter months when there was

Fort

William. They would then take trade goods back west to exchange

for more furs. The other group known as the "pork

eaters" were usually much bigger in size and quite

physically strong. They would pack the 90 lb. fur packs into

canoes and paddle them east to Montreal, and bring back trade

goods. There were many points at which the fur packs had to be

portaged around bad water and falls. Each man was expected to

carry a minimum of 2 packs, and many carried three. During the

great rendezvous in mid-summer, when the voyageurs from the west

and the voyagers from the east both arrived at the at the same

time, there might be several thousand people at the Fort. During

the cold winter months when there was little or no activity, there might not be more

the 40 people at the fort. To feed the large gathering during the

summer months, extensive farming was conducted in and around the

Fort. Horses, cattle, sheep, chickens, a large vegetable garden

and an assortment of animal fodder were needed. This all required

buildings. Barns, houses, a great dining hall, store rooms, and a

power magazine. Carpenters, brick layers, and coopers were hired.

Then there were the clerks, accountants and stockmen responsible

for keeping track of the trade goods and getting the furs ready

for shipment east. On top of this was a small group of mostly

Scottish men who managed the entire operation for the Montreal

owners. Although located deep in the wilderness, Fort William was

not lacking for

little or no activity, there might not be more

the 40 people at the fort. To feed the large gathering during the

summer months, extensive farming was conducted in and around the

Fort. Horses, cattle, sheep, chickens, a large vegetable garden

and an assortment of animal fodder were needed. This all required

buildings. Barns, houses, a great dining hall, store rooms, and a

power magazine. Carpenters, brick layers, and coopers were hired.

Then there were the clerks, accountants and stockmen responsible

for keeping track of the trade goods and getting the furs ready

for shipment east. On top of this was a small group of mostly

Scottish men who managed the entire operation for the Montreal

owners. Although located deep in the wilderness, Fort William was

not lacking for amenities. Many types of craftsmen made their

living. plying their trade within the palisade walls. In addition

aristocratic visitors often arrived to review the business for an

extended period of time. As we rounded the corner into the fort

we came upon several buildings, each with its own actors. The

schooner Captain, the Doctor, each with a story to tell. With

accents practiced, they would enter into lively conversations

with both other actors or any of the visitors who happed to ask a

question. Always quick to act confused when anything prior to

their period was mentioned, such as computers, airplanes,

telephones, or cars, these

amenities. Many types of craftsmen made their

living. plying their trade within the palisade walls. In addition

aristocratic visitors often arrived to review the business for an

extended period of time. As we rounded the corner into the fort

we came upon several buildings, each with its own actors. The

schooner Captain, the Doctor, each with a story to tell. With

accents practiced, they would enter into lively conversations

with both other actors or any of the visitors who happed to ask a

question. Always quick to act confused when anything prior to

their period was mentioned, such as computers, airplanes,

telephones, or cars, these  docents presented a perfect image of the time

they so richly presented. As we entered the trading floor, we

were greeted with an assortment of dry goods, hardware, knives

and muskets, all arranged neatly on shelves. Each had a price, so

many plus (pronounced plew). A plus equals a credit which is paid

for by one beaver pelt, with some ability to slide the value one

way or another. Gold, silver or currency were not used in the

Fort. The basic unit of payment was one beaver skin. From the

docents presented a perfect image of the time

they so richly presented. As we entered the trading floor, we

were greeted with an assortment of dry goods, hardware, knives

and muskets, all arranged neatly on shelves. Each had a price, so

many plus (pronounced plew). A plus equals a credit which is paid

for by one beaver pelt, with some ability to slide the value one

way or another. Gold, silver or currency were not used in the

Fort. The basic unit of payment was one beaver skin. From the  trading

floor, we moved to the fur packing storehouse. Here, hanging form

the rafters and on poles throughout the entire warehouse were

pelts of every description, from beaver to arctic fox. These were

the real thing, actually captured from poachers over the years

and lent to the museum by the authorities. In the middle of the

room was a fur press. Beaver skins were compressed until a pile

of them weighed 90 lbs. They were then wrapped and tied and

became a basic fur pack which the voyagers had to carry. A young

man demonstrated the required strength as he showed how two packs

were carried using a head strap. With a mighty heave he stood

straight up under 180 lbs of beaver fur and staggered around the

room for a complete circle. The strain on his body was enormous

and evident by the protruding veins in his neck. An offer for

others in the room to try the back pack fully loaded was not

accepted by anyone.

trading

floor, we moved to the fur packing storehouse. Here, hanging form

the rafters and on poles throughout the entire warehouse were

pelts of every description, from beaver to arctic fox. These were

the real thing, actually captured from poachers over the years

and lent to the museum by the authorities. In the middle of the

room was a fur press. Beaver skins were compressed until a pile

of them weighed 90 lbs. They were then wrapped and tied and

became a basic fur pack which the voyagers had to carry. A young

man demonstrated the required strength as he showed how two packs

were carried using a head strap. With a mighty heave he stood

straight up under 180 lbs of beaver fur and staggered around the

room for a complete circle. The strain on his body was enormous

and evident by the protruding veins in his neck. An offer for

others in the room to try the back pack fully loaded was not

accepted by anyone.